On this page:

About Team-Based Learning™

Our school has successfully implemented Team-Based Learning™ in all of our preclinical courses and most of our clerkships. We are the first school in the country to adopt so fully this educational strategy.

Team-Based Learning™is an instructional strategy based on procedures for developing high performance learning teams that can dramatically enhance the quality of student learning by:

- Enhancing problem-solving skills

- Replacing or reducing lecture time

- Ensuring that students are prepared and on time to class

- Creating a remarkable amount of energy in the classroom

- Promoting team work

- Encourage critical thinking

Team-Based Learning™is a well-defined instructional strategy developed by Dr. Larry K. Michaelsen that is now being used successfully in health professions education. The Team-Based Learning™ method allows a single instructor to conduct multiple small groups simultaneously in the same classroom.

Learners must actively participate in and out of class through preparation and group discussion. Class time is shifted away from learning facts and toward application and integration of information. The instructor retains control of content, and acts as both facilitator and content expert. The Team-Based Learning™ method affords the opportunity for assessment of both individual and team performance.

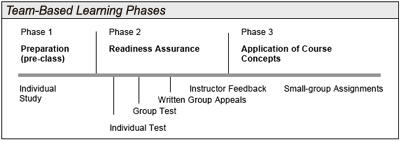

As an instructional method, Team-Based Learning™ consists of repeating sequences of three phases:

- In Phase 1, learners study independently outside of class to master identified objectives.

- In Phase 2, individual learners complete a multiple-choice exam to assure their readiness to apply Phase 1 knowledge. Groups of 6-7 learners then re-take this exam and turn in their consensus answers for immediate scoring and posting.

- In Phase 3, groups collaborate on in-class application assignments. At designated times; all groups simultaneously share their groups' answers with the entire class for easy comparison and immediate feedback. This stimulates an energetic total-class discussion with groups defending their answers and the teacher helping to consolidate learning.

Team-Based Learning™ emphasizes three keys to effective active learning:

- Individual and group accountability

- Need and opportunity for group interaction

- Motivation to engage in give-and-take discussion

Team-Based Learning™ Collaborative (TLC)

Public site of the Team-Based Learning™ Collaborative

The TBLC is an organization of health sciences faculty whose mission is to promote and support the use of Team-Based Learning™ in medical education. The membership includes basic scientists, health professions educators, and educational specialists who have variable degrees of experience with Team-Based Learning™.

Activities of the TLC:

- Team-Based Learning™ workshops & seminars

- Peer mentoring

- A case bank of faculty development and classroom teaching materials

- Research on Team-Based Learning™ and evaluation methods/tools

Testimonials from Students

These are some testimonials from first and second year medical students about their experiences with TBL:

Kudos

"TBLs were the best aspect of this course. I really learned a lot from working with my classmates and looked forward to the times we would study together and go through the group assessments together."

"I really enjoyed the Team-Based Learning sessions. Both working with my team and also answering questions about actual cases was very helpful in learning the material."

"Team-Based Learning was useful because we were able to use microscopes and work our way through cases and apply our knowledge."

"I thought that incorporating a real life event (the Hank Gathers story) into a team-based learning activity was a great way to give us some clinical insight into the kind of decisions we will have to be making as physicians."

"One of the strengths of this course was the TBL Group Readiness Assurance Tests. I learned the most from my peers when trying to determine group answers."

"Team-Based Learning has always been one of my favorite aspects of Wright State."

"Team-Based Learning was a good learning experience as always. I like how they are becoming more clinical in their scope."

"Always pushing our limits of knowledge. Good experience."

"Excellent resource and good use of time to help in understanding and solidifying important aspects."

Suggestions

"Questions about looking up statistics are a waste of our time. It's nice to know but we'll never remember them & by the time we get into practice most of them will probably have changed anyway. Also, I would have liked to spend more time on more common diseases rather than the relatively obscure syndromes."

"I really don't appreciate professors walking around and giving people hints. If a hint is going to be given out, it needs to be given out to the whole room and at both sessions."

"The faculty expected us to make clinical judgments when we have not been exposed to that clinical experience or knowledge. When 15 out 16 teams miss a question (and the team that got it right did some guessing) because we lack the clinical knowledge that shows it is either a bad question or we weren't taught the information and should be thrown out."

"The supplementary reading for TBL was interesting and extremely applicable, however, it was a little vague. It would have been nice if it had been a little clear regarding our expectations."

"In an effort to make some of the questions more challenging, they are becoming more obscure and less representative of how much the students know. It is hard to stump a roomful of medical students, so I understand how it is difficult to make challenging questions."

"OK, I LOVE TBLs and always learn a lot. However, they loose their luster when we are actually expected to learn new material within a limited time period for a GRADE. There have been a few instances where I felt the question required knowledge not presented in the course and not appropriate for such a short period of time. These questions are best left for the end of the TBL as an instructional exercise not to be graded."

Testimonials from Faculty

These stories were collected from across the nation by Dr. Boyd Richards, Baylor College of Medicine, on the impact of Team Based Learning on faculty:

A Physician

"Team learning has been the most significant influence on my career. It has brought the "fun" back into teaching. Students once slept through didactics; they are now engaged during every session. They come to class prepared, studying beforehand from books they previously never purchased. I get to know the students better as I see them interacting. Scores on the NBME subject exam have significantly improved. Team learning has led to collaborations with peers in and outside my institution. I have assisted colleagues in setting up team learning courses. I have published and presented my results nationally. I am inundated with requests for materials, to give workshops, or do consultations. Team learning has so many advantages over conventional methods, I regret I don't have the time to help more people learn about it."

A Basic Scientist

"Baylor's first team learning workshop came just at the right time for my institution. We believed that the LCME would cite us for insufficient student-centered learning. We began a monthly team learning interest group. With Baylor's help, we conducted a local workshop. We instituted team learning in a limited manner in 2001-2002. It was a disaster, but we learned a lot about what did and didn't work. We presented at AAMC and Baylor's second annual workshop. In 2002-2003, we successfully began a new team learning longitudinal course. Team learning is now a modest staple within the curriculum. Students still worry about grading issues but in general, things are going well. The team learning collaboration has made my education research career. I have learned a lot and hopefully contributed to others. It has expanded my research from my discipline into educational scholarship. Because I led the school's team learning interest group, I became the person identified with the method. As a result of this exposure, I was appointed a member, and eventually chair, of our Education Policy Committee."

A Medical Educator

"I can say that, first, team learning has connected me to a new group of education professionals in a way that has not happened for a while. Secondly, it has opened a new avenue of potential research interests, especially in the area of professionalism development in small group settings. And finally, it has given a real and demonstrated meaning to the concept of collaboration within a community of scholars."

A Physician

"I was asked by a colleague to assist her in a randomized control trial study of team learning. From this experience, I found team learning to require a deeper understanding of the material even from me, and more advance preparation. It has made me so much more aware of learner engagement. Now I am much more in tune with trying to engage the learner in each teaching session, and can see how to do it so much more effectively. It also allows me to give constructive feedback to others to improve their ability in this area. Along with other things, team learning has peaked my interest in medical education and I have recently become associate program director. In the last two weeks, I discussed with two other faculty my frustrations with having all these ideas but no support. Because of the team learning study, and my deeper exposure to medical education, I am now aware of this deficiency in our system. Now the three of us hope to push even harder for support to accomplish scholarship in our respective areas. Overall, team learning has been a wonderful experience. I am hopefully participating in my first national workshop this November. I have been involved in a randomized controlled trial. I am discovering a whole new exciting world of academic medicine."

A Basic Scientist

"So the experience with team learning for me overall has been interesting and mixed. On the one hand the initial negative response of students was shocking and extremely stressful. On the other, I still find great potential in the exercises and I think I'm working bugs out in the way we do them such that they become not only viable but valuable for our students. Although having been through the wringer initially, I'm feeling quite positive about the exercises now. I presented a poster at the 2004 IAMSE meeting on the student response to team learning in HCB, and will be writing it up and submitting it hopefully in the next few months. We also intend to write-up the faculty experience."

A Basic Scientist

"Participating in the team learning collaborative exposed me to a completely different group of faculty. I was introduced to others doing educational research and who were very experienced. This introduced me to possible topics for research and the various approaches (quantitative vs. qualitative) to educational research. The success of the team learning project increased my visibility around the country and several times schools specifically asked for me to work with them on team learning. I believe that this increased my prestige within my department and if it did not, I at least felt that it did. My work with team learning was one of the reasons that I was able to move to a new school and become department chair. On many occasions our Executive Dean has described to visitors my experience with team learning as one of the reason that they wanted to hire me. Now that I am here, he uses me as an example of how the educational environment is being improved."

A Basic Scientist

"At the workshop, it became apparent that the TL method could remedy our problems. I had two other faculty members dissatisfied with our current small group format and willing to give this a try, so it was a 'no brainer' to convert our small group sessions to a TL format.

We did a full-scale implementation right away with 12 TL sessions during our nine-week course and had the TL work count 25% of the course grade. The faculty and the students were very positive about the use of TL in the course. We have continued to use TBL for three years with some tweaking, but essentially the same format. As a group, the faculty using TBL have learned quite a bit about what works and doesn't work. The interactions we have between the faculty here as well as with those at other institutions have been very helpful.

We have presented a report of our TBL experience and have a paper in press. I have also, of course, shared our experience with others here in TBL workshops."